The prevalence of both osteoporosis and obesity has been increasing over the past few decades: 55% of Americans over age 50 have weakened bones in the clinical form of osteopenia or osteoporosis (per National Osteoporosis Foundation), and nearly two-thirds of adults are overweight. Coincidence? Maybe not.

The prevalence of both osteoporosis and obesity has been increasing over the past few decades: 55% of Americans over age 50 have weakened bones in the clinical form of osteopenia or osteoporosis (per National Osteoporosis Foundation), and nearly two-thirds of adults are overweight. Coincidence? Maybe not.

Researchers have found similarities in the biochemical pathways between the two conditions. The same progenitor cells develop into osteoblast and adipose cells, prompting one article (http://www.nature.com/nrrheum/journal/v2/n1/full/ncprheum0070.html ) to rhetorically ask "is osteoporosis the obesity of bone?"

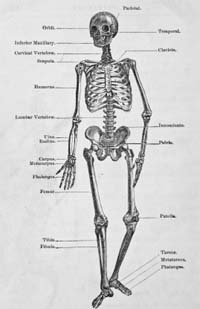

Statistical analysis shows a correlation between body mass index and bone mineral density (BMD). Scientists have also found positive correlations between an increase in adipose tissue (fat) and BMD. Genes have been identified that are thought to connect bone metabolism and obesity. However, other analyses suggest that gene effects associated with increased fat mass are associated with larger, stronger femora, which would tend to work against the obesity-osteoporosis hypothesis.

Experts suspect that one link between obesity and osteoporosis occurs through leptin, a hormone involved in the body’s weight control mechanism. Levels of leptin are higher in people with lot of adipose tissue, i.e. in obese individuals. Researchers found that leptin affects bone density; the effect is different at different parts of the skeleton. Mice raised with artificially low levels of leptin end up with shorter legs and lower bone density, and more spongy bone, but the same mice have longer backs, and thicker and denser backbones.

Mice raised with lowered levels of the leptin hormone have higher levels of bone resorption due to osteoclasts. Most of the research in the connection between fat hormones and bones involves leptin, but there are also indications that other regulatory biochemicals (cytokines) affect bone formation and destruction. Nervous system signaling molecules also influence bone growth and turnover as well as energy metabolism.

Bone cells may in turn produce cytokines and other biochemical signaling molecules that affect metabolism and obesity. It has been shown that osteocalcin directly affects the pancreas and other tissues. Like so much of anatomy and physiology, obesity is a function of environment and genes and the correlation with osteoporosis is likely a combination of behavioral and heredity factors. However, the correlation has been demonstrated in mice raised in identical environmental conditions, which suggests genetic factors are paramount.

Purely from a structural engineering standpoint, one would expect to see heavier people with thicker and stronger bones. One would predict bone morphology resulting in stronger bones just because of the increased mechanical loading in overweight individuals.

Action plan for women in their 40s and 50s

Spanish language version of this page